Reduction Machines

Sources

Search

Contact

Home

The VAMs

What Is A VAM?

Interest & Rarity

Hubs to Dies

New VAM Variety

Obverse Dies

Reverse Dies

Clashing

Reduction Machines at the Mint

It took us a great deal of time and effort before we found someone who had actually researched the reduction machines in use at the Mint. To understand the making of VAMs you need to understand the coin production process, and we knew intuitively that this was critical.

For the most part we found that some collectors believe the Mint used the Janvier Reduction Machine to create Morgan Dollar hubs and dies, but it did not come into production until 1906, well after the end of the first Morgan Dollar run. This is some 25 years after our 1881-O coin was produced, so something else had to be used to produce the coins. The Janvier machine was a vast improvement over its predecessors, but was not there. The Mint's mastery of the Janvier machine did not come until later.

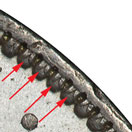

From 1836, and then into the early 20th century the engravers would only use the Contamin or Hill equipment to make hubs of the primary obverse and reverse device. The engraver would make a large sculpted pattern of the Liberty or Eagle, and this could be reduced to the size required for the dollar or other coins of a different diameter. What they would cut was the hub with only this feature and not the entire coin design. The hub would then be punched into a die. Lettering, stars and dates were added by hand, punching each into the resulting die to create the master die. For this reason you will often find the pantograph referred to as a portrait lathe.

So we know with certainty that Morgan Dollars were made in a process where only the primary devices were cut into the master hub, and all other devices were added with punches. Based on the Mint's time-line of equipment acquisition, we know it was the Hill reduction equipment and neither the Contamin nor the Janvier.

The pantograph had another benefit to engravers in that they could work on a much larger bas-relief pattern rather than working on the hub or die directly. No doubt that hand engraving a die would have been tedious at best.

All three of the pantographs described here are classified as third generation machines.

Links to these articles of interest can be found on our sources page.

Before the Days of the Pantograph

Before the days of the pantograph the job of the engravers was truly art. A sketch of the coin design was made and then approved by the Director of the Mint. Once approved, the engraver carved the primary device into the master die by hand.

All dates, stars, and other embellishments were added not to the master die but to the working dies. The addition of these devices so late in the process all but ensured that there would be both errors and die varieties.

This methodology was in place until 1836 when the first Contamin pantograph was purchased for the Philadelphia Mint.

Contamin Pantograph

The Contamin Pantograph was in use at the Mint from 1836 to 1867. The first name of Contamin has been lost to history and we have found no source with more detail.

This was the first die-engraving pantograph that used a rotating cutter. This in effect transformed the pantographic into a mechanically controlled milling machine, instead of a copying lathe. The inventor, Contamin (the remainder of his name has been lost to time) was French. Contamin redesigned or adapted an earlier French mechanical pantograph, created by Jean Baptiste Dupeyrat. Contamin’s engraving pantograph was in widespread use for over 60 years and its use overlapped the invention of the next generation for years.

Hill Pantograph

In England machinist C. J. Hill began work on his die-engraving pantograph in the early to mid-1800s. He was possibly inspired by a Contamin, or a reducing machine improved by James Watt at Soho Mint. After development, Hill sold the rights to his machine to a William Wyon. The Hill machine differs from any others we have seen because it has the galvano and hub laying horizontally rather than vertically.

The U. S. Mint purchased its first Hill pantograph from William Wyon in September of 1867. It was received and placed in use in 1868. However, mint engravers still use the Hill pantograph like they had used their Contamin. Perhaps it was comfort with the old process, but they only used it to make hubs of primary design devices from oversize models. Lettering and numbers were added by hand.

In the 1867 Annual Report Mint Director Henry R. Linderman wrote “this important and interesting machine … reduces copies of bas-reliefs by which the freedom of execution of the larger model is susceptible in the hands of the artist, can be preserved in the most minute proportions … to the face of the coin for which it is designed.”

The photograph is from the Royal Mint in Brittan and is the only known picture of this important piece of equipment we have been able to locate. On May 11, 2015 we did receive positive confirmation from a Mint representative that this is the Hill lathe.

Please note that the reducer was treadle powered, making control difficult for the operator and probably requiring some significant skill to master. It has also been reported that the U. S. Mint had their equipment modified, so it likely looked somewhat different. We contacted the U. S. Mint in Philadelphia in May 2015 to see if they have a photograph of their model, but so far there has been no response.

Janvier Pantograph

The Philadelphia Mint purchased its first Janvier pantograph at the recommendation and insistence of President Theodore Roosevelt. The President had learned of its existence from sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. This reduction lathe, or portrait lathe, was the invention of the Frenchman Janvier et Duval.

Saint-Gaudens model for the high relief $20 gold coin was to be the first American coin reduced on the Janvier machine. Medallic Art founder Henri Weil, who had instructed mint engravers on how the Janvier pantograph was operated. He was later asked by Saint-Gaudens assistant, Henry Hering, for assistance in lowering the relief.

Chief engraver Charles E. Barber declared that Saint-Gaudens’ model was still unworkable, the relief was still too high, and it was ultimately lowered for the two varieties of this coin in 1907.

In this video from The Royal Mint there is a Janvier reduction machine briefly shown in use, a rare glimpse into the past. Apparently it was in use for over 100 years.

In the illustration on the left the important features of the machine are evident. The arm with the tracing mechanism on the right and the cutting bit on the left are in their proper place for work. A little more difficult to see, but there, are the belts running across the front. These belts allowed the cutting head more freedom as the design was cut. Since the tracing head was traveling a longer distance as you moved out from the center of the design. The belts allowed for more accurate synchronization between the two heads. This was the improvement over the Hill machine that precipitated the change.

An interesting side note on the Janvier is that it was perhaps too good. Apparently the machine was so accurate and so well made that once acquired it never needed replacing. According to the British Royal Museum the company went out of business for lack of obsolescence. This can be confirmed because we see advertisements for them today some 100 years after their introduction.

Getting Started

Collecting The 1881-O

The 1881-O VAMs