The Environment

Sources

Search

Contact

Home

We take health and wellbeing almost for granted today but the United States and our environment were very different in the late 1800s. By today's standards we would probably liken the environment to that of a third-world country. That is an unfair comparison because the advances in science, technology, and healthcare we enjoy today just had not taken place. When you read about the nineteenth century you begin to appreciate the twentieth and twenty-first. But it would be accurate to say that prior to 1900 "Life was hard and then you died!".

Temperatures and Humidity

Waste Removal

Pollution

Elsewhere in this web site we have touched on the difficulty employees must have faced because of heat and humidity that accompanies the working conditions in New Orleans.

If you have lived in the South then you know that if the temperature doesn't get you the humidity will, especially in mid summer. Now imagine working in heavy clothing, in an un-air conditioned building next to a fire or furnace all summer. That environment was the New Orleans Mint in a nutshell.

You didn't need a wind chill calculator when you worked there, but a heat index calculator might help. According to Intellicast Weather the historical average low temperature is never below 43 degrees, and the historical average highs reach 91 degrees. Record highs in the winter can reach 90 degrees, while record highs in the summer reach 102 degrees. The city also gets about 63 inches of rain each year, unless there is a major hurricane and then the averages go out the window.

Humidity on the other hand is a real treat. The average humidity level is 61% and even though it does fluctuate, the range is fairly narrow. In May through October when the average temperature is 80 degrees or above, the average "feels like" temperatures are 90, 98, 103, 103, and 82. On many days the real temperature would have been in excess of 100.

Extended heat and humidity had to have an effect on quality and working conditions. We have no way to factor in the working conditions in areas where melting, assaying, or refining were performed. Add to all this mix the use of steam power for all the equipment and you get another fun fact.

The picture above is of the Adjusting Department in 1897. Now imagine working in 100 degree heat in multiple layers of clothing. These women weighed individual planchets one at a time until they had "adjusted" millions of them. Notice there is a single light bulb and a light from a transom over the door. There were two windows behind the women on the right side of the picture and one behind the photographer, but cross ventilation may have been lacking.

The group of happy men in this picture is identified as the Smelting Room employees. Imagine working in these conditions in the summer heat! They all appear to be somewhat "shell shocked" and rightly so.

Yellow Fever

Referred to as "Yellow Jack" or the "Yellow Plague" it is a viral disease that results in symptoms like we now associate with the flu. But the insidious nature of the disease is that victims normally felt better after five or so days, only to have it return and cause internal bleeding. The yellow refers to skin color changes as a result of liver damage.

During the Civil War the incidents of Yellow Fever declined in New Orleans to only 11 for the four years. This was primarily attributed to a decline in shipping during the war years.

After the war the port of New Orleans brought prosperity to the region, but it also brought an unwanted health concern in Yellow Fever. From 1817 until 1905 (reliable statistical dates) over 41,000 people died from Yellow Fever in New Orleans alone. The most likely culprit would have been infected sailors or passengers arriving on ships from the Caribbean, Cuba, and South and Central America. Once ashore the swarms of mosquitoes then help spread the disease.

On eight occasions there were more than 1,000 deaths (1819, 1847, 1853, 1854, 1855, 1858, 1867, and 1878), with the decade of the 1850s being the worst. New Orleans holds the record for the last outbreak in the United States in 1905.

On eight occasions there were more than 1,000 deaths (1819, 1847, 1853, 1854, 1855, 1858, 1867, and 1878), with the decade of the 1850s being the worst. New Orleans holds the record for the last outbreak in the United States in 1905.

Just three years prior to 1881 there had been an outbreak where 4,046 people died. And then the decade of the 1880s was very quiet with only 4 deaths over the decade. But in 1878 the arrival of the fever brought a mass exodus from the city and one fifth of the residents left from precaution or fear.

The disease was not limited to New Orleans and other Southern ports continued to see outbreaks about the same time. A vaccine was eventually developed and better understanding of disease, germs, and elimination of mosquito breeding grounds also helped eradicate the disease in the U. S. Better screening of passengers and sailors arriving from likely foreign ports also contributed to the decline in cases. But when you read the next column on pollution from horses you will understand the challenges much better.

Hurricanes

Annually there are discussions about hurricane preparedness in New Orleans, and the same was true in the 1800s. The picture below is of the dock in New Orleans after one of the hurricanes in August of 1881. According to NOAA there were no major hurricanes that year and no direct strikes on the port. So this is ancillary damage from some close call.

There were two close calls that year. The first hurricane on August 4 went east of New Orleans up through Mississippi. The second storm on August 12 went west of New Orleans and made landfall in Galveston, Texas. Either of these could have had a tidal surge that caused this damage.

But the clear message for the Mint workers was that they lived below sea level and from August through October of every year there was the threat of work and life disruption from weather related events.

Perhaps the health issues of New Orleans in the 1800s can best be understood at the confluence of all the waste that had to be carried from the city via drainage canals. In those days no distinction was made between various forms of waste, so the canals were viewed as a universal drainage vehicle. They were a mixture of animal and human waste, industrial waste, garbage, and anything else that citizens felt needed to be thrown or floated away.

These drainage issues were not unique to New Orleans and in general accepted practice. Complicating the health situation was swarms of mosquitoes that descended on the city, primarily at night. They were so thick that the sound of their buzzing would often drown out conversation.

These drainage issues were not unique to New Orleans and in general accepted practice. Complicating the health situation was swarms of mosquitoes that descended on the city, primarily at night. They were so thick that the sound of their buzzing would often drown out conversation.

Sitting below sea level and below the water level of the Mississippi River, the soil in the area was always saturated. Drainage was a particular challenge because the waste had to be lifted up and out, usually to the swamp above the city. Before and immediately after the Civil War the extent of the drainage efforts was the installation of several steam powered paddle wheels that "lifted" the drainage material up and out of the city over levees. But the cumulative capacity of these machines was inadequate much of the time and there was no money to implement other solutions.

Sitting below sea level and below the water level of the Mississippi River, the soil in the area was always saturated. Drainage was a particular challenge because the waste had to be lifted up and out, usually to the swamp above the city. Before and immediately after the Civil War the extent of the drainage efforts was the installation of several steam powered paddle wheels that "lifted" the drainage material up and out of the city over levees. But the cumulative capacity of these machines was inadequate much of the time and there was no money to implement other solutions.

One would think that the Yellow Fever epidemics would have motivated citizens to find a solution, but politics and technological issues seemed to always get in the way. After the Yellow Fever epidemic of 1878 several solutions were proposed, but none implemented. Usually measures that were approved were inadequate or never fully implemented because of costs and resulting bankruptcies.

In 1881 the city had a chance to contract with a newly formed company, the "New Orleans Drainage and Sewage Company". However arguments over the use of pipes in the wet soil slowed the discussion. Even though approved, nothing was ever done to increase the drainage. The sole effort of the era may have been to increase the number of steam powered pumps to increase the evacuation of waste from the city.

And then if all this were not enough there were chamber pots. The prescribed method of disposing of overnight human waste was to bring it down and dump it into your privy. But often the privy would be full or near capacity, or the person doing the dumping was just lazy and they would throw the waste from a window into the street. Women of the era carried parasols to guard against chamber pots as much as the sun. It was difficult to look presentable after someone dumps a chamber pot on you.

It was not until the 1890s when the realization that adequate water and drainage was needed to fuel economic growth that something finally got done. The inconvenient truth is that a city that exists below sea level with poor drainage and unpredictable weather should have never been built or should move to higher ground up river.

Drinking Water

Although the positive effects of filtration and chlorination of water were known in Europe in the 1880s, the first chlorination of a public water supply in America was not until 1908. The lack of adequate water treatment in New Orleans led to the death of over 5,000 people in 1849.

New Orleans has some special drinking water challenges. The city sits over a large aquifer, but the soil above the aquifer is basically a bog and the water becomes unpleasantly discolored. Desalination of sea water was only a dream on any scale and a full 80 years into the future for any practical use.

That left rainwater and the Mississippi River as the logical sources of water for New Orleans. As much as 300 billion gallons of water flows by the city each day in the river, so this seems like the most logical source. But without purification how to make the water usable was a challenge.

Water from the Mississippi was stored by residents in large earthenware jars. The sediments were allowed to settle to the bottom of the jars, and the "clean" water then used for drinking and other household purposes. The value of boiling water was known at the time, so one would assume that drinking water was boiled.

But New Orleans was last in the chain of cities on the Mississippi River, so the water from the river contained the accumulation of all the upstream waste from Minnesota to the Gulf.

Rainwater was a better source of usable water and was widely valued and recognized for its importance. Large cisterns were made from cypress and used to store rainwater. The rainwater was collected from rooftops and channeled into the cisterns. The availability of this source would depend on a number of factors: rainfall, roof surface area, cistern size, runoff efficiency, and evaporation were all important. Smaller homes and business concerns may have had no more than the short supply from a rain barrel. The high water table in the area made large in-ground cisterns impossible.

Rainwater was a better source of usable water and was widely valued and recognized for its importance. Large cisterns were made from cypress and used to store rainwater. The rainwater was collected from rooftops and channeled into the cisterns. The availability of this source would depend on a number of factors: rainfall, roof surface area, cistern size, runoff efficiency, and evaporation were all important. Smaller homes and business concerns may have had no more than the short supply from a rain barrel. The high water table in the area made large in-ground cisterns impossible.

But even with all this effort there were issues. Cholera, typhoid fever, yellow fever, dysentery, and other diseases were all linked to the quality of water.

We are sure that there were all forms of pollution in the 1800s but we only want to look at one, horse manure. This form of pollution is so foreign to us now in the era of cars that the issues are almost unimaginable.

But the Model T Ford did not appear until 1908 and is given credit as the first affordable automobile. Cars had been around for decades, but not in large quantities and certainly not as a mass horse replacement.

But the Model T Ford did not appear until 1908 and is given credit as the first affordable automobile. Cars had been around for decades, but not in large quantities and certainly not as a mass horse replacement.

In 1881 in New Orleans the horse would have been the primary form of transportation. They pulled carriages, wagons, street cars, and were ridden individually. Horses were literally everywhere, and horse manure accompanied their travels.

In 1881 in New Orleans the horse would have been the primary form of transportation. They pulled carriages, wagons, street cars, and were ridden individually. Horses were literally everywhere, and horse manure accompanied their travels.

A typical horse produces from 15 to 30 pounds of manure per day, so just how many horses were there in 1881 and how much manure? We have been unable to locate an accurate source of horse population data for New Orleans in 1881, so we will use a little extrapolation to get there.

The horse population in the United States advanced throughout the late 1800s and peaked in 1915 at just over 26 million animals. Today there are about 9 million, up from a low of 3 million in 1960. But today horses are recreational and not functional. In 1880 the population of New York was 1.2 million while the population of New Orleans was 215,000 or about 6 to 1. It is estimated that the horse population of New York was 170,000 and we might assume from that number that in New Orleans there were about 28,000.

Those horses produced about 630,000 pounds of manure every day. That is 315 tons of manure to remove every night just to be able to open for business the next morning. Horse manure was a breeding ground for flies that carried disease in all major cities, so manure removal was critical. In dry weather it became airborne, in wet weather it just turned to an offensive muck, and the smell was beyond belief. Mixed in with all this was horse urine, another source of odor and disease. Those same horses produced 7,000 gallons of urine each day that just soaked into the streets.

Shop keepers often did a little cleanup in from of their businesses, but there was still the final removal issue.

Major cities had city sanitation crews, but these were often supplemented with prisoners from local jails to try to stay ahead of the problem.

The removal work was also done after business hours from necessity by what was known as "night soil" crews. We have no evidence to support the disposal process in New Orleans, but in New York there were blocks of the city used for manure storage until it could be removed. These could be stacked as high as 65 feet at times. Since New Orleans is below sea level the removal of manure to an area outside the city probably posed a somewhat unique disposal issue.

Also, the average lifespan of a working horse of the era was between two and four years. When they died they were left to rot in the street until the carcass could be hauled off more easily. This obviously provided another breeding ground for disease and a disposal challenge since an adult horse could weigh as much as 1,200 pounds.

As seen in this picture children often played around horse carcases, spreading disease to them and others.

As seen in this picture children often played around horse carcases, spreading disease to them and others.

By modern standards this seems almost unimaginable, but it was just accepted urban life in the 1800s.

Like it or not, Henry Ford might be the greatest environmentalist of all time. We might not like the fumes from cars, but we can guarantee you it is preferable to what we would have with horses if they were still our primary form of transportation.

The Aging 1D

Submissions

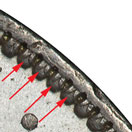

Clashed Denticle

Date Issues

Encyclopedia

New Orleans and the Mint in 1881

The Devolving 5

One and Done

Two and Through

Fakes

Die Fingerprints

Pricing

The Devolving 27

New Orleans and The Mint in 1881

The Civil War

Politics

The Economy

Environment

Organization

Personnel

Coinage

The Jobs

Politicians

Getting Started

Collecting The 1881-O

The 1881-O VAMs